Herniated disc

A herniated disc (herniated nucleus pulposus) is a spinal disease in which part of the core of the intervertebral disc exits the outer layers of the disc (anulus fibrosus) and presses on nerves or the spinal cord, which may cause pain.

Learn more about herniated discs in this article: What exactly is a herniated disc and what are its symptoms? What causes a herniated disc? What are the possible treatments and therapies? And much more …

What is a herniated disc?

Intervertebral discs are fibrocartilaginous joints located between the vertebrae. When intact, they serve to balance out the pressure stress on the spine.

A herniated disc (ICD-10 code: M50-M51) is the exiting of a part of the gelatinous core (nucleus pulposus) of the intervertebral disc through the outer layers of the disc (anulus fibrosus). The prolapsed material presses on nerves (spinal nerve) or the spinal cord and causes pain.

With good fluid balance, vertebral discs account for 25% of the length of the spine. If vertebral discs become brittle in advanced age, the overall spine becomes shorter, which reduces mobility.

The likelihood of a herniated disc is approx. 3.5% for people under 35 years of age. It increases to 20% for people aged 45 to 55 years. Men are affected twice as often as women. 90% of herniated discs occur in the lumbar spine (L-spine). The remaining 10% almost exclusively affect the cervical spine (C-spine). Herniated discs in the thoracic spine are extremely rare (Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie up2date 2016 - Orthopaedics and Trauma Surgery up2date).

This is not the same as the preliminary stage of a herniated disc, the disc protrusion. In contrast to a herniated disc (prolapse), the core of the intervertebral disc does not exit completely during the protrusion, but penetrates through small cracks

in the anulus fibrosus. Intervertebral disc damage often goes completely unnoticed. 55% of the working population have a disc protrusion, and 30% even have a herniated disc, which go unnoticed due to the absence of pain (Pflugmacher & Koch 2013).

If a herniated disc causes pain, however, it is usually unbearable.

What is the difference between a herniated disc and lumbago?

Lumbago should not be confused with a herniated disc. Lumbago (acute lower back pain) is a sudden piercing pain in the lower back. The sometimes severe pain in the lumbar region is often misinterpreted as a sign of a herniated disc by those affected. In rare cases, it may be a symptom of a herniated disc, but usually it has more harmless causes. In lumbago, the supplying nerve of the lumbar spine is irritated due to muscle tension, joint blockages, or displaced discs, and thus causes pain.

The typical symptoms of lumbago are:

- hardened back muscles

- stiffening of the lumbar spine

- low-back pain

- pressure-sensitive spinous processes (pressure on protruding sections of the spine causes pain)

The pain leads the affected person to assume an adaptive posture that causes less pain. However, this causes further tensioning of the spine, and thus worsens the overall condition. Prompt treatment is thus required to avoid unnecessarily long periods of pain. Depending on the exact cause, lumbago is usually treated either by an orthopaedic surgeon who sets the vertebrae, or with heat treatment, or pharmaceutically by means of analgesics.

Symptoms of a herniated disc

Symptoms manifest themselves differently, depending on the extent and area of the prolapse, and whether the nerve is compressed. Pain may be severe and persistent, but it may also be brief and temporary, disappearing in a few days or weeks. A herniated disc does not always cause pain. It may develop without noticeable signs and resolve itself. If the herniated disc is large or is situated in an awkward position, it may press on the spinal nerve or the spinal cord. This may cause neurological symptoms, such as sensory disorders or paralyses.

Herniated discs occur most frequently in the lumbar spine (approx. 90%), followed by the cervical spine. A herniated disc in the thoracic vertebrae is extremely rare. This is due to the natural curvature of the lumbar and cervical spine (lordosis). These

regions are more mobile, and are thus exposed to greater stress. The congenital angle of the thoracic spine (kyphotic angle) makes it less susceptible to overload and wear, making intervertebral disc injuries in this area less likely.

Depending on the extent and area of the spine that is affected by the herniated disc, the symptoms may involve pain in the back, legs/feet or arms/hands, tingling in the back, buttocks, legs, or paralysis.

Symptoms of a herniated disc in the cervical spine (C-spine):

- upper back pain

- sensory disorders in the shoulders, arms, and hands

- tingling in the shoulders, arms, and hands

- paralysis symptoms in the shoulders, arms, and hands

Symptoms of a herniated disc in the lumbar spine (L-spine):

- lower back pain

- sensory disorders in the back, legs, or feet

- tingling in the back, legs, or feet

- paralysis symptoms in the legs or feet

In rare severe cases, a prolapse in this area may cause the following:

- impaired bowel movement

- urination disorders

- numbness in the anal and genital area

- paralysis symptoms in the legs or feet

These specific symptoms are also known as cauda equina syndrome, conus medullaris syndrome, or cauda-conus syndrome. If symptoms of this type occur, a physician should be consulted immediately. It is a medical emergency that usually requires surgical treatment.

Prompt action is also required if back pain or paralysis is caused by an accident, if there is a history of tumours, or with osteoporosis, with weight loss and fever, and when pain intensifies at night (Glocker 2012).

The symptoms vary depending on the location and extent of the herniated disc. Prolapses in the cervical spine affect the upper half of the body, while prolapses in the lumbar spine affect the lower half of the body. Herniated discs are not always accompanied by pain, and may go unnoticed.

First aid for a herniated disc

In the acute stage of a herniated disc, the strain on the back should be relieved as much as possible. However, this does not mean complete bed rest! Careful training in a horizontal position that is gentle on the back, using isometric exercises (holding exercises), can be very beneficial and promote regeneration.

Heat treatment for the affected back area using heated cushions/lamps, and treatment with electricity, are also good options for improving one’s condition.

Diagnosis: herniated disc

A number of tests are required to determine exactly whether the symptoms are due to a herniated disc. The case history is taken first. The patient is asked questions about the location and type of pain and, if applicable, the type of limitation they experience.

Neurological diagnostic tests are then carried out to determine which nerve is affected. This is to test sensory functions (numbness or tingling), strength, reflexes, and range of movement. The goal is to find out which spine section is affected by the herniated disc.

Since each nerve root supplies a specific muscle and a specific area of the skin, key muscle group tables can support the patient’s physician in making the diagnosis (Pflugmacher & Koch 2013):

| nerve root | key muscle group | impaired reflex | skin areas (dermatomes) |

C5 | biceps brachii muscle (elbow flexion) | biceps reflex | shoulder area (deltoid muscle area) |

C6 | flexor carpi radialis muscle (wrist flexion) | brachioradialis reflex | inner side (radial) of the upper arm and forearm down to the thumb |

| C7 | triceps brachii muscle | triceps reflex | back of the forearm down to the 2nd-5th finger |

C8 | intrinsic muscles of the hand | triceps reflex | underside of the forearm down to the little finger |

TH1 | spreading the fingers | inner side of the upper arm | |

| L1/L2 | iliopsoas muscle (hip flexion) | cremasteric reflex | groin, anterior and interior section of the femur |

| L3 | quadriceps femoris muscle (knee extension), adductor muscle, longus, brevis, magnus (hip adductors) | patellar reflex | anterior section of the femur |

| L4 | quadriceps femoris muscle (knee extension) | patellar reflex | outer femur above the knee (patella) to the inner side of the lower leg |

| L5 | extensor hallucis longus muscle | posterior tibial reflex | outer part of the lower leg and the back of the foot down to the big toe |

| S1 | triceps surae muscle (lowering the foot) peroneus muscle (lateral foot lift), gluteus maximus muscle (hip extension) | Achilles reflex | rear lower leg down to the outer side of the foot |

Imaging tests are used for a more accurate diagnosis. Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or, in rare cases, myelography (X-ray with contrast agent) can show the spinal cord and nerve roots directly. There is also the option of

testing the nerve conduction velocity (NCV). This procedure is used, for example, for patients with pareses,

or in the case of a suspected slowing of nerve conduction due to compression in the spine.

Differential diagnosis

A differential diagnosis is made in order to differentiate it from other similar diseases. The following diseases cause symptoms similar to those of a herniated disc:

- stenoses (spinal stenosis, neural foraminal stenosis): narrowing of a nerve canal

- inflammation/entrapment of the sciatic nerve

- pain radiating from the sacroiliac joint

- arthrotic changes in the vertebral bodies (damage due to wear)

- peripheral arterial occlusive disease (PAOD): constriction of blood vessels in the legs

A herniated disc is usually diagnosed in three steps. The case history is taken first. This is followed by a clinical neurological examination. Imaging techniques, such as CT or MRI, and the testing of nerve conduction velocity eventually enable an accurate diagnosis.

Causes of a herniated disc

A herniated disc can have various causes. In most cases, it is the result of wear and the subsequent inability of the intervertebral disc to store water. Drying out of the intervertebral disc is part of a completely natural aging process. If water can no longer be absorbed, the intervertebral disc becomes brittle. The brittle material tears more easily under stress, causing a protrusion of the core of the intervertebral disc (nucleus pulposus). However, this ageing process does not occur at the same pace in all people. A herniated disc may occur relatively early in life in people with genetic predispositions.

In rare cases, a herniated disc may also be caused by an overload or pathological load distribution. Usually, however, this only occurs after a spinal injury.

Risk factors for a herniated disc

In general, there are the following risk factors:

- lifestyle

- training behaviour

- genetic predisposition of a person (the key risk factor)

Obesity leads to increased day-to-day strain. Insufficient movement and poor sitting posture weaken the back and thus the ability to relieve the stress on the vertebral discs. A pathological load distribution, especially during strength training, may put heavy stress on the spine.

The previously described tendency of the vertebral discs to become brittle in old age can be passed on from generation to generation. It thus represents the greatest risk for herniated discs. The greatest risk, therefore, cannot be influenced.

Progression of a herniated disc

The consequences of a herniated disc may last for different periods and are different for each person, which makes it difficult to accurately describe its progression.

Not all patients will experience pain as a result of a herniated disc. This type of spinal disorder may also go completely unnoticed. The pain is not always the same, and does not always have the same intensity. It may be short and piercing or persistent and twinging, or paralysing. Very severe pain may require hospitalisation and infusion therapies.

In about 90% of cases, the symptoms (pain, weakness, tingling) disappear on their own after 8 weeks at the latest. The body breaks down the material prolapsed from the vertebral disc, and the compression disappears.

If the symptoms persist for more than 6-8 weeks, or if severe paralysis occurs right from the start, conservative measures may reach their limits and surgery may be required.

Preventing a herniated disc

It is hardly possible to prevent a herniated disc. Due to the marked genetic risk component, prevention measures consist primarily of physical training and a lifestyle that is gentle on the back.

The following tips may be of help:

- training of back and abdominal muscles to strengthen the spinal column and relieve stress on the vertebral discs

- proper lifting and carrying of objects

- correct sitting position to relieve stress on the back

- avoiding sitting for longer periods without breaks

- ergonomic seats and the right mattress

- paying attention to exercising correctly

- back-friendly sports in the case of suspected disc issues, e.g. swimming, cycling, etc.

Preventing a herniated disc is very difficult in practise. Strong genetic predisposition severely limits the possibilities of prevention. However, muscle strengthening and ergonomic improvements in one’s daily routine may have a positive impact.

Treatment of a herniated disc

Conservative procedures

The vast majority of herniated discs can be treated well with conservative medicine. This means, among other things, the use of physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or sports therapy. The aim is to rebuild and strengthen the muscles (especially in the back or stomach area) that are required for the stability and protection of the spine. Pain is treated primarily pharmacologically. Painkillers help prevent the adaptive posture, and may thus facilitate faster healing.

Another form of conservative treatment is heat therapy. Heat relieves pain, promotes blood circulation and thus the metabolism in the body, and relaxes tense muscles.

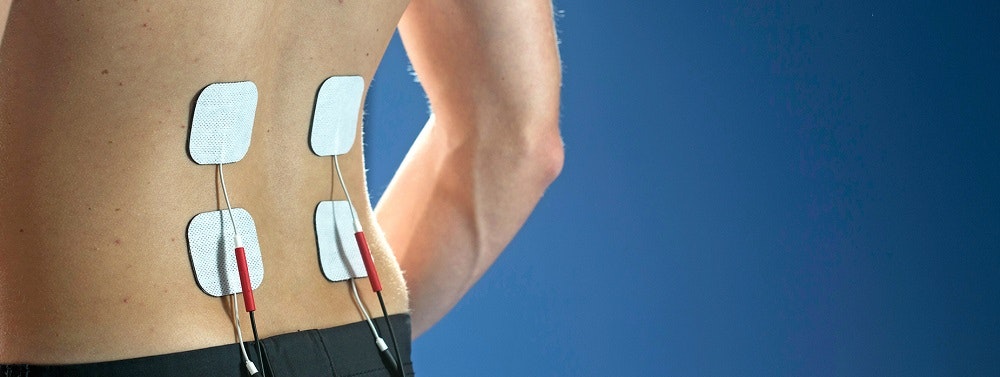

Electrotherapy is a good add-on treatment in this regard. Electrical stimulation is an efficient and modern rehabilitation option. It can be used in addition to physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or sports therapy, and also for the treatment of pain.

When is surgery necessary?

Surgery could help if the symptoms of a herniated disc persist after 6-8 weeks, despite pharmacological treatment or exercise therapy. Special attention should be paid to symptoms of a paralysis. They are a particularly strong indication and require immediate intervention.

The usual reasons for surgery are as follows:

- very rapid deterioration of the condition

- rapidly increasing pain

- paralysis symptoms, especially in the genital and anal area

- bladder and fecal incontinence

Rehabilitation after a herniated disc

Pain relief

The vast majority of herniated discs can be easily treated with conservative therapy, i.e. physiotherapy and occupational therapy, sport, heat therapy, or medication. Regeneration of a herniated disc usually takes about 6-8 weeks. If there is still no improvement after this time, it is strongly recommended to see a physician again.

The top priority in the treatment of a herniated disc is pain relief and the resolution of symptoms. If the prolapse is painful, the affected person automatically assumes an adaptive posture to relieve pain. The resulting problem is that this unnatural posture further tenses the strained back muscles and worsens the pain. To prevent this, a physician first prescribes pain and anti-inflammatory medication and, in more severe cases, also local anaesthetics.

Heat may also have an analgesic effect. Red light lamps, or simply warm clothing, promote blood circulation and relax the painfully tense muscles.

Massages, electrotherapy, and physiotherapy may be used to treat a herniated disc in order to relieve pain.

Movement therapy

The next step in the treatment of a herniated disc is physiotherapy or occupational therapy. It can begin after a relatively short time. Sport is not only possible, but also desirable, and may also accelerate the healing process. However, care should be taken to choose the right sport. Sports that are gentle on the back, such as swimming, cycling, or water gymnastics, may have an extremely positive impact.

The goal of exercise therapy and sports is to strengthen the back and abdominal muscles in order to restore the stability of the spine and to protect it. Gentle movements may also help the affected person to abandon the adaptive posture, and thus interrupt the pain cycle. A therapist can efficiently treat the pain caused by tension by applying massages and connective tissue techniques.

Physiotherapeutic treatment is particularly important if the nerve compression has caused paralysis of the arms or legs. Therapy can train the affected muscles and help restore lost functions (e.g. elbow flexion).

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) for muscle strengthening following a herniated disc

Electrotherapy after a herniated disc

Electrotherapy is another treatment option for herniated discs. It is both effective and comfortable. Electrical stimulation of the right muscles can strengthen the back and relieve pain. Electrotherapy devices also offer the biofeedback function, which can improve coordination and movement. This means that electrotherapy is not only able to support rehabilitation after a herniated disc, but can also help prevent further prolapses.

In the case of a herniated disc with paralysis (paresis), the focus is on restoring strength and functions. If the symptoms are so severe that the affected person can hardly move the muscle(s), functional electrical stimulation (EMG-triggered multi-channel electrical stimulation) can help with the relearning of movements.

If the muscle is completely denervated (the nerve is squeezed so much that it cannot temporarily conduct impulses or move the muscle), there are special currents that will keep the muscle strong until the nerve can conduct again.

Numerous studies have shown that electrotherapy is an excellent option for significantly shortening the therapy time in every phase of rehabilitation.

If you are interested in continuing education on functional electrical stimulation and wish for a STIWELL® training directly at your institute or online, please contact us

Find out how functional electrical stimulation with the STIWELL® can be used to strengthen muscles following a herniated disc.

Glocker FX (2012): Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie, Zugriff am 5.7.2018 unter https://web.archive.org/web/20140222061135/http://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/030-058l_S2k_Lumbale_Radikulopathie_2013_1.pdf.

Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie up2date (2016): Der lumbale Bandscheibenvorfall, Zugriff am 6.7.2018 unter https://www.thieme.de/de/orthopaedie-unfallchirurgie/der-lumbale-bandscheibenvorfall-109184.htm.

Pflugmacher, R., Koch, P. (2013). Degenerative Erkrankungen. In: Ruchholtz, S. & Wirtz, D. C. (Hrsg.). Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie essentials: Intensivkurs zur Weiterbildung. (2.Aufl.) Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 676-690.

Pflugmacher, R., Koch, P. (2013). Untersuchungstechniken. In: Ruchholtz, S.

& Wirtz, D. C. (Hrsg.). Orthopädie und Unfallchirurgie essentials:

Intensivkurs zur Weiterbildung. (2.Aufl.) Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag, 658-663.