Facial nerve palsy

Facial nerve palsy (also known as facial paresis) refers to the paralysis of muscles that are activated (innervated) by the facial nerve. The paralysis is usually on one side, and affects movements of the forehead, the eye, the nose, and the mouth.

The paresis may be caused by central or peripheral damage, such as a stroke, tumours, inflammation, or traumas. The treatment of facial nerve palsy is particularly important if the condition has existed over a longer period, or if the recovery is incomplete.

Learn more about facial nerve palsy: What therapy methods are available and what are the chances of a long-term recovery? Definition, numbers, causes & diagnostics at a glance ...

What is facial nerve palsy?

Facial nerve palsy (ICD code: G51.0, P11.3, S04.5) describes the paralysis, usually one-sided, of certain facial muscles, especially mimetic muscles, which are innervated by the facial nerve (n. facialis).

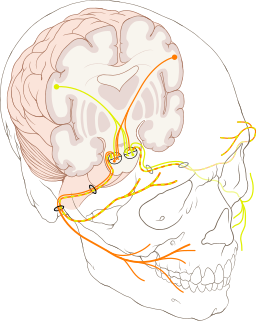

The facial nerve is the seventh (VII) of the twelve (XII) cranial nerves. It is paired, which means that there is a facial nerve on both the right and left sides of the body. Cranial nerves are those nerves that originate from the brain (cranial nerve nuclei) and run directly to the end organ (muscle, gland, etc.). All other nerves that innervate the periphery (arms, legs, and torso) have an indirect course, which means that they need to connect to the spinal cord.

The facial nerve innervates the mimetic muscles (muscles of the forehead, eye, nose, mouth, and a cutaneous muscle of the neck - the platysma), the stapedius muscle in the auditory canal, parts of the ‘swallowing muscles’ (posterior sections

of suprahyoid muscles), as well as the anterior two-thirds of the tongue for taste perception (sensory) and almost all head glands (visceromotor).

Forms of facial paralysis

Due to the complex structure of our brain and nerves, damage in many places may lead to the appearance of a facial paresis, i.e. paralysis of facial muscles.

If the connection between the cerebral cortex and the motor nuclei in the brain stem (more precisely, the pons) is affected, this is called a central or supranuclear palsy. Damage to the facial motor nucleus itself (nuclear paresis) is rare.

The nerve is most often damaged in its course below the cranial nerve nuclei down to the end organ (infranuclear). This is a peripheral facial nerve palsy. Facial nerve palsy usually means a peripheral paralysis of certain mimetic muscles

due to an impairment of the facial nerve (nervus facialis).

Central vs. peripheral facial nerve palsy

The central palsy is usually associated with other symptoms of central damage, such as paralysis of the arms or legs. Damage above the facial motor nuclei causes contralateral (opposite) impairment of the innervated mimetic muscles. Although weaker, the muscles of the upper half of the face are still intact, so that it is possible to frown and close the eyelid. This is because the muscles of the upper half of the face are innervated only to a two-thirds extent by the opposite facial motor nuclei, and to a one-third extent by the equilateral facial motor nuclei (Hacke 2016).

In contrast, the symptoms of peripheral facial nerve palsy are always on the same side (ipsilateral) as the damage, and the forehead and eyelid muscles are usually affected also. Furthermore, non-motor fibres may also be affected, which would impair the taste and/or gland function.

Causes of facial nerve palsy

Facial nerve inflammation

Facial nerve palsy may be caused by inflammation. In this case, it is called a facial nerve inflammation. Here, the peripheral nerve is inflamed due to viruses or bacteria. The possible pathogens are:

- Neurotropic viruses (viruses that infect nerve cells, e.g. HIV)

- Zoster viruses (in the context of zoster oticus)

- Borellia bacteria (neuroborreliosis)

Peripheral facial nerve palsy

Paralysis of facial muscles due to peripheral damage, i.e. an impairment of the facial nerve (nervus facialis) itself, may have various causes. In 60-75% of cases, the cause is unknown (idiopathic). The remaining 25-40% are due to a variety of causes (Finkensieper et al. 2012 ).

Possible causes of the development of peripheral facial nerve palsy:

- Idiopathic

The cause of the genesis is unknown here.

- Traumatic

The facial nerve is injured, often due to fractures of the petrous portion of the temporal bone.

- Tumours

In most cases, the nerve is damaged by the pressure of the tumour. Various tumours may affect the nerve:- Tumours of the parotid gland (parotid tumours)

- Schwannoma of the facial nerve

- Acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma)

- Pearl tumour (cholesteatoma)

- Tumours in the cerebellopontine angle

- Spread of tumour cells in the meninges (neoplastic meningitis)

- Iatrogenic (caused by medical intervention)

The damage to the facial nerve may also occur as a possible complication of surgical removal of the parotid gland or the submandibular gland.

- In the context of the following syndromes

- Guillain-Barre syndrome (acute inflammatory disease of peripheral nerves), especially in Miller-Fisher syndrome (a variant of GBS)

- Carey Fineman Ziter syndrome (congenital brain malformation)

- Möbius syndrome (congenital malformation syndrome)

- Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (inflammatory artery disease)

- Heerfordt syndrome (inflammation of the parotid and lachrymal glands)

Facial nerve palsy may also develop in the context of metabolic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus (especially in connection with arterial hypertension), and in pregnancy (especially in the last trimester) (Heckmann et al. 2017).

Depending on the cause, facial nerve palsy may also have more specific names:

- Bell's palsy in idiopathic facial nerve palsy

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome in the context of zoster oticus

- Mona Lisa syndrome during pregnancy

Central facial paresis

If central damage, i.e. a dysfunction in the brain, leads to paralysis of the facial muscles, this can also have several causes:

- stroke

- multiple sclerosis

- tumours

- etc.

A sudden paralysis of facial muscles, whether it is due to a peripheral or a central cause, should always be considered an emergency. It is necessary to seek medical advice immediately.

Depending on the location of the damage (peripheral or central), there are different causes that may be responsible for the paralysis. Most often, however, the cause is unknown. In this case, it is called idiopathic facial nerve palsy (or Bell's palsy).

Symptoms of facial nerve palsy

Since the peripheral nerve is usually affected on one side, the symptoms are usually one-sided, i.e. the facial nerve palsy affects one side of the face. Bilateral facial nerve palsy occurs only in rare cases, for example, in patients with borreliosis.

The main symptom of damage to the facial nerve is the paralysis of mimetic muscles, which becomes visible as follows:

- Drooping corner of the mouth

- Drooping eyelid

- Frowning is not possible

Eye muscle paralysis often makes closing the eyelid impossible. There is a risk that the eye will dry out, which must be treated symptomatically .

Apart from the muscles, damage to the facial nerve may also affect other functions of the nerve. Impairments may manifest themselves as follows:

- Decreased tear formation

- Sensitivity to noise (hyperacusis due to damage to the stapedius muscle)

- Diminished saliva production

- Impaired taste perception (anterior two-thirds of the tongue)

Pain, numbness, or tingling of one half of the face are not caused by damage to the facial nerve, but may occasionally be observed in some lesions due to the involvement of other nerves (trigeminal nerve).

Progression & prognosis of facial nerve palsy

The duration and chances of a recovery depend greatly on the cause, nature, and extent of the facial nerve palsy.

The usually spontaneous idiopathic facial nerve palsy has a relatively good prognosis. In 71% of cases, the paralysis usually resolves itself within days or weeks, less often within months. Only about 29% of affected persons have lasting motor deficits. 16% develop synkinesias, which include, for example, simultaneous involuntary movements of the eye when closing the mouth (Peitersen 2002). First-time, one-sided facial nerve palsy also has a good prognosis, especially if the affected persons are ‘young’ (< 60 years), and the nerve is only partially damaged (neurapraxia).

If the nerve is severely damaged or completely severed (axonotmesis), as may be the case, for example, for severe fractures of the petrous bone, complete resolution (remission) of the symptoms is rather unlikely. Incomplete resolution may subsequently lead to severe asymmetries or synkinesias in the face, which are usually very stressful for the affected person.

The paralysis of muscles in the area of the mouth is not only psychologically stressful, but also limits everyday functions. The flaccid muscles cause saliva or liquids to spill out of the corner of the mouth (‘drooling’) when drinking, or cause food to remain in the cheek. The reduced strength may also affect speech. In most cases, the person concerned can no longer form sounds properly, which makes it difficult to understand them (dysarthria/speech disorder).

Symptomatic therapy and rehabilitation are particularly important for patients with severe injuries, permanent deficits, and problems with eating or speaking.

Diagnosis: facial nerve palsy

Facial nerve palsy is usually diagnosed by a neurologist. In some cases, it may also be necessary to consult an otorhinolaryngologist.

The physician begins with a physical examination, which should give information on the form and cause of the facial nerve palsy. Of all the possible symptoms of facial nerve palsy, the function of facial muscles is the easiest to check clinically. The affected person may be told to perform the following tasks before the diagnosis is made (Hacke 2016):

- Frown

- Open/close your eyes

- Wrinkle your nose

- Mouth/lips: pucker your lips, smile, whistle, puff out your cheeks (including on one side)

Bell's phenomenon is observed if the affected person cannot close his or her eye completely. This means that the upward movement of the eyeball (and thus the white of the eye) is visible, because the eyelid is not completely closed. This movement is a physiological defensive reflex of the eye to protect the cornea (which only occurs in 75% of the population).

Severe pareses can be detected even before mobility is tested. The initial visual examination (inspection) reveals eyelids that have a different width, a drooping eye and corner of the mouth, and asymmetrical facial wrinkles.

Facial nerve palsy is diagnosed by visual and clinical examination, followed by electrophysiological examination, transcranial magnetic stimulation, lumbar puncture, and, rarely, imaging of the head.

The physician has further diagnostic options for a more detailed diagnosis:

- Electrophysiological examination

(Electroneurography of the distal facial nerve/electromyography of mimetic muscles)

It clearly indicates whether the facial nerve is damaged and the muscles are weak. - Transcranial magnetic stimulation (at the exit from the brain stem)

Above all, it may indicate a peripheral problem in the early phase. - Lumbar puncture:

Lumbar puncture is performed to obtain a sample of the cerebrospinal fluid. If certain pathogens are suspected, the CSF diagnostics can provide more information. - Head imaging (cranial CT or MRI)

It is usually not required. It is only performed in cases of suspected central damage (stroke, tumour, etc.).

Therapy for facial nerve palsy

If the cause is known, the focus is on the treatment of the underlying disease. If the cause is unknown, as is the case with the idiopathic facial nerve palsy, standard pharmacological treatment involves the administration of glucocorticoids and/or antiviral medications.

In some cases, however, symptomatic therapy may be necessary, for example, when the eyelid does not close properly. Artificial tears, eye ointment, and/or a protective eye dressing are used to protect the eye from drying out. In the event of persistent problems with eyelid closure, it may sometimes be necessary to apply gold or platinum weights to the eyelid.

Botulinum toxin (Botox for short) is used in some cases for the symptomatic treatment of synkinesias (simultaneous involuntary movement of the eye when moving the mouth). It must be re-injected every 3-4 months to achieve lasting results.

In the case of severe and persistent pareses, microsurgical techniques are sometimes applied for the reconstruction of the facial nerve, e.g.

- using the intact nerve of the opposite side (cross-face facial nerve suture)

- or by connecting to other nerves (hypoglossal-facial jump nerve anastomosis).

The free (dynamic) muscle transfer of the forehead muscle (frontalis muscle) is also an option. Since research in this area has not yet been exhausted, there are increasingly other options for surgical treatment.

The therapy is individual, depending on the cause. Glucocorticoids are administered in cases of frequent idiopathic facial nerve palsy. If the cause has been established, the underlying disease is treated. Symptomatic and surgical treatment is paramount in the event of incomplete recovery and a high degree of severity.

Treatment of facial nerve palsy

Therapy for facial muscle paralysis is recommended in the case of central pareses, long-term peripheral pareses, and as a complementary therapy alongside the pharmacological treatment. Exercises in speech therapy, physiotherapy, and/or electrical stimulation serve to restore functions, improve movement disorders (dyskinesia), strengthen the muscles, and increase self-efficacy for psychological reasons.

Speech therapy, physiotherapy & occupational therapy

Exercises to train mimetic muscles are usually performed by speech therapists, but they may also be performed by physiotherapists and occupational therapists. The exercises may be performed when emotions are expressed (especially laughing), and/or in front of a mirror. Examples of exercises to train mimetic muscles:

- Look angry/knit your eyebrows

- Look astonished/raise your eyebrows

- Close your eyes completely (gently/tightly) or partially

- Open your eyes wide

- Blink

- Raise/wrinkle your nose

- Open your nostrils wide

- Lower your nose/narrow your nostrils

- Smile (with your mouth closed/open)

- Show your teeth

- Purse your lips (whistle/pucker your lips)

- Puff out your cheeks

- etc.

Various exercises for the forehead, eyes, nose, and/or mouth are selected individually for each patient and serve to improve functions (Pereira et al. 2011). There is evidence for this, especially in chronic cases with a moderate paresis (Teixeira et al. 2011). For patients with severe paresis, starting exercise therapy early leads to positive effects with regards to the severity and duration of regression (Nicastri et al. 2013).

Electrotherapy & biofeedback

In the case of peripheral pareses, the focus is on treatment with special currents (low frequency, long pulse duration). When the nerve is completely severed, especially after surgical procedures, the focus is on electrotherapy to protect the muscles from degradation (atrophy) and from abnormalities of the connective tissue.

The misconception that the stimulation hinders reinnervation (restoration of nerve function) has been refuted in recent studies (Carraro 2018). Initial studies even demonstrate that low-frequency electrical stimulation promotes innervation (Gordon et al. 2016).

As the healing process progresses and the muscles become active again, synkinesia is often observed (simultaneous involuntary movement of the eye when closing the mouth, etc.). Biofeedback therapy may help to prevent these involuntary movements (Pourmomeny et al. 2014). It is even more efficient than the mirror therapy on its own (Dalla Toffola et al. 2012), although a combination with a mirror is certainly advantageous (Cardoso et al. 2008). In general, good training results are achieved when motor effects are reinforced (Bernd et al. 2018), as is the case with the biofeedback therapy. Biofeedback can also be used in a home-based therapy (Volk et al. 2014).

In the case of central paralyses of facial muscles, functional electrical stimulation (EMG-triggered multi-channel electrostimulation), biofeedback, or a combination of both is used. Exercises cover one or two muscles (1-channel or 2-channel) and serve to restore functions or prevent involuntary movements.

If you are interested in continuing education on functional electrical stimulation and wish for a STIWELL® training directly at your institute or online, please contact us

Find out how functional electrical stimulation with the STIWELL® can be used to treat facial nerve palsy.

Bernd, E., Kukuk, M., Holtmann, L., Stettner, M., Mattheis, S., Lang, S. & Schlüter, A. (2018). Ein neu entwickeltes Biofeedbackprogramm zum Gesichtsmuskeltraining für Patienten mit Fazialisparese. HNO, 1-7.

Cardoso, J. R., Teixeira, E. C., Moreira, M. D., Fávero, F. M., Fontes, S. V. & de Oliveira, A. S. B. (2008). Effects of exercises on Bell's palsy: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Otology & Neurotology, 29(4), 557-560.

Carraro, U. (2018). Exciting perspectives for Translational Myology in the Abstracts of the 2018 Spring Padua Muscle Days: Giovanni Salviati Memorial – Chapter IV-Abstracts of March 17, 2018. European journal of translational myology, 28(1), 49-78.

Dalla Toffola, E., Tinelli, C., Lozza, A., Bejor, M., Pavese, C., Degli Agosti, I., & Petrucci, L. (2012). Choosing the best rehabilitation treatment for Bell’s palsy. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med, 48(4), 635-642.

Finkensieper, M., Volk, G. F., & Guntinas-Lichius, O. (2012). Erkrankungen des Nervus facialis. Laryngo-rhino-otologie, 91(02), 121-142.

Gordon, T. & English, A. W. (2016). Strategies to promote peripheral nerve regeneration: electrical stimulation and/or exercise. European Journal of Neuroscience, 43(3), 336-350.

Hacke, W. (2016). Neurologie. (14. Aufl.). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag.

Heckmann, J. G. et al. (2017). S2k-Leitlinie: Therapie der idiopathischen Fazialisparese (Bell’s palsy). In: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie. (Hrsg.). Leitlinien für Diagnostik und Therapie in der Neurologie. Online: www.dgn.org/leitlinien (abgerufen am 07.08.2018).

Nicastri, M., Mancini, P., De Seta, D., Bertoli, G., Prosperini, L., Toni, D., ... & Filipo, R. (2013). Efficacy of early physical therapy in severe Bell’s palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 27(6), 542-551.

Peitersen, E. (2002). Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Oto-Laryngologica, 122(7), 4-30.

Pereira, L. M., Obara, K., Dias, J. M., Menacho, M. O., Lavado, E. L. & Cardoso, J. R. (2011). Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical rehabilitation, 25(7), 649-658.

Pourmomeny, A. A., Zadmehre, H., Mirshamsi, M. & Mahmodi, Z. (2014). Prevention of synkinesis by biofeedback therapy: A randomized clinical trial. Otology & Neurotology, 35(4), 739-742.

Teixeira, L. J., Valbuza J. S. & Prado G. F. (2011). Physical therapy for Bell´s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 7:CD006283.

Volk, G. F., Finkensieper, M., & Guntinas-Lichius, O. (2014). EMG Biofeedback Training zuhause zur Therapie der Defektheilung bei chronischer Fazialisparese. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie, 93(01), 15-24.