Tetraplegia

Tetraplegia is a spinal cord injury in the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar area. The severity of symptoms varies, depending on the underlying causes, and the location and extent of the damage.

Learn more about tetraplegia and the available therapy or treatment methods. Also learn more about the causes, symptoms, long-term chances of recovery, and the diagnostic process, etc.

What is tetraplegia?

Tetraplegia (also called spinal cord injury) means damage to the spinal cord (ICD-10 CODE: G82, S14, S24, S34). The spinal cord is located in the spinal canal and is protected by spinal meninges and liquid (cerebrospinal fluid). The spinal cord is an accumulation of nerve fibres. They are responsible for transporting information back and forth between the brain (central) and the periphery (e.g. muscle, skin, etc.).

The spinal cord conducts the following information from the brain to the body (efferents):

- Movement information (motor nerves): movement is generated when this information arrives at the muscle

The spinal cord conducts the following information from the body to the brain (afferents):

- Feedback on pain, temperature, sensation of touch and pressure (protopathic sensibility)

- Feedback on the fine sense of touch or tactile discrimination (epicritic sensitivity): Touching two points close to each other is perceived as two separate stimuli, and not one.

- Feedback on the sense of position (proprioception): What is the body’s position?

As a rule, afferents and efferents form a circuit to and from the brain, and there is a constant balancing between the expected and the actual situation. However, not all information has to travel via the brain. Afferents and efferents are sometimes directly connected to each other. This direct connection is known as a reflex (e.g. patellar reflex).

In addition to movement and sensation, the spinal cord is also responsible for information about the cardiovascular system and internal organs (autonomic nerves). The autonomic nerves regulate the heartbeat, breathing, digestion, and much more.

Damage to the spinal cord may cause impaired sensation and movement as well as dysfunctions of the internal organs. The symptoms depend on the extent (incomplete/complete) and the level of spinal cord damage.

In terms of motor functions, paralysis at a higher level (e.g. in the cervical spine) usually causes paralysis (plegia) of all limbs. This paralysis of arms and legs is called quadriplegia (tetraplegia). Paralysis at a lower level (e.g. in the lumbar spine) causes plegias in the legs. This is called paraplegia. It is slightly more frequent than tetraplegia (Swiss Paraplegic Association 2012).

If a paralysis (plegia) is not completely pronounced, it is called a paresis (incomplete paralysis). Thus the terms tetraparesis and paraparesis are occasionally used.

Learn more about the forms of tetraplegia >

Causes of tetraplegia

Tetraplegia can generally occur in all diseases affecting the spinal cord. A distinction is made between traumatic and non-traumatic causes, the latter being less frequent.

Trauma

Injuries (traumas) are the most common cause of spinal cord injury. In up to 70% of cases, accidents in daily life are responsible for a spinal cord injury. Road accidents and falls, as well as sports accidents, are the most common cause.

Other non-traumatic causes

Other less common causes of spinal cord injury are:

- Masses or compression (pressure)

As a rule, they squeeze the nerves, which are then no longer adequately supplied with oxygen and nutrients. The lack of supply causes damage to the respective nerves. They are caused by:- Tumours

- Herniated disc in the spinal canal (extradural/extramedullary = outside the spinal meninges and the spinal cord)

- Syringomyelia (formation of cavities within the spinal cord = intramedullary)

- Vascular disorders caused by

- reduced blood flow (ischaemia, as with a stroke)

- bleeding (haemorrhages)

- formation of gas bubbles (e.g. when surfacing too fast after a dive: decompression/caisson/divers' disease)

- Metabolic (metabolism)/ toxic (poisons) causes,

e.g. due to long-standing vitamin B12 deficiency (subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord) - Neurodegenerative diseases,

such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) - Transverse myelitis (spinal cord inflammation), e.g.

- in patients with multiple sclerosis

- in patients with poliomyelitis (infantile paralysis)

- in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases (such as lupus)

- caused by bacteria or viruses (e.g. in the case of neuroborreliosis, herpes zoster, or HIV)

- in the context of tumour diseases (paraneoplastic)

- in the context of infectious diseases (parainfectious): Rubella, measles, hepatitis A, B, or C, etc.

Although the pathogen is not the cause of the spinal cord inflammation (myelitis) here, it is often present as a side effect.

Tetraplegia may be caused by trauma (especially accidents), compression (especially due to tumours or herniated discs), inflammation (transverse myelitis), circulatory disorders (ischaemia), or bleeding (haemorrhages). Tetraplegia may also occur in the context of neurodegenerative diseases (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, etc.) and metabolic disorders (vitamin B12 deficiency).

Forms of tetraplegia

A distinction is made between a complete or incomplete paralysis, depending on whether all nerve fibres of the spinal cord are affected or only some of them. Incomplete paralysis has sub-types depending on the location of the lesion. Damage may occur

in the anterior section (anterior spinal cord syndrome), in the posterior section (posterior spinal cord syndrome), in the centre (central cord syndrome), in the bone marrow, or on one side (Brown-Séquard syndrome).

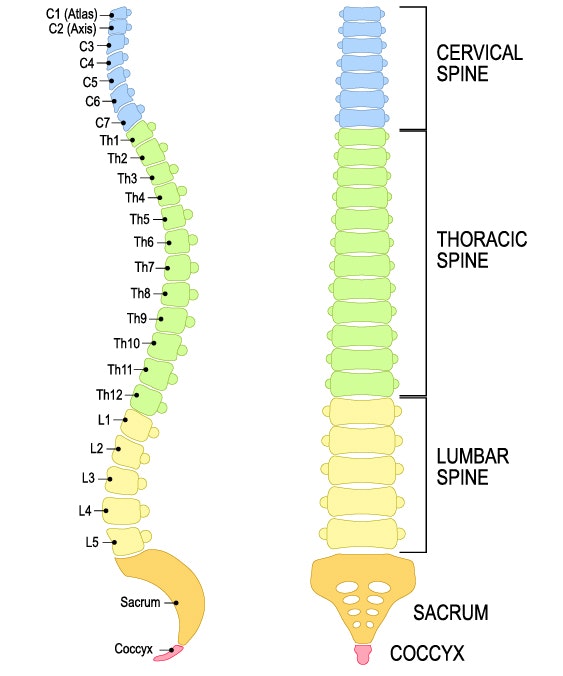

Complete or incomplete lesions in the spinal cord rarely affect the entire cord, but only one or more segments. Lesions of the spinal cord are usually classified according to their location:

- Cervical spine:

The cervical spine comprises segments C1 to C8, with nerve roots exiting above the corresponding vertebrae. - Thoracic spine:

The thoracic spine includes segments TH1 to TH12, with these and all the deeper nerve roots exiting below the corresponding vertebrae. - Lumbar spine:

The lumbar spine is divided into L1 to L5. - Sacrum:

This is the sacral region with sections S1 to S5. - Coccyx:

This region contains the coccygeal vertebrae (Co1).

The level of injury, in turn, results in different types of damage. An injury to the upper segments results in quadriplegia/tetraparesis, which causes paralyses in the arms and legs. Lower damage causes paraplegia/paraparesis, i.e. paralysis of the legs. An injury to the lumbar part of the spinal cord (from Th12/L1) may cause the conus medullaris syndrome, which affects mainly the bladder, bowel, and sexual functions. An injury to the lower end of the spinal cord (cauda equina) causes paralysis of the legs, in addition to bladder, bowel, and sexual dysfunctions.

The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale is used to classify acquired tetraplegia. The extent of paralysis determines the following categories (American Spinal Injury Association 1992):

- ASIA A - complete: No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5.

- ASIA B - incomplete: Sensory (sensation), but not motor (movement) function, is preserved below the level of injury and includes S4/S5

- ASIA C - incomplete: Motor function (movement) is preserved below the level of injury, and most muscles are either unable to move, or can move only slightly against the force of gravity.

- ASIA D - incomplete: Motor function (movement) is preserved below the level of injury, and most muscles are able to move against the force of gravity, or even against resistance.

- ASIA E - normal: Normal functions (sensory and motor)

Symptoms of tetraplegia

Depending on the type of tetraplegia (complete or incomplete), movement and/or sensation is impaired. The control of internal organs may be impaired in the event of lesions above the 5th thoracic vertebra due to the separation of the sympathetic nervous system. In general, the higher the paralysis, the more body parts are affected.

Motor symptoms (movement):

- spastic paralysis (paresis) below the location of damage

- flaccid paralysis (paresis) at the location of damage

Sensory disorders (sensation):

- impaired pain, temperature, touch, and pressure sensation (protopathic sensibility)

- impaired fine sense of touch or tactile discrimination (epicritic sensibility)

- impaired sense of position (proprioception)

Autonomic disorders (internal organs):

- neurogenic bladder disorders

- rectal voiding disorders

- erectile dysfunction

- trophic disorders, sweat gland secretion

- impaired peripheral circulation/temperature regulation

Progression of tetraplegia

Limited motor skills/acute consequences

In the immediate aftermath of the trauma, all muscle functions below the injury location are lost, and reflexes are absent (spinal shock). There is also tachycardia (fast heartbeat), while the pulse can be easily felt and the hands are well supplied with

blood (differential diagnosis to distinguish from classic shock). This pseudo-flaccid paresis persists for a few days to weeks before spasticity (excessive muscle tension) develops due to a reorganisation process.

Long-term damage and life expectancy

Depending on the nature and severity of tetraplegia, there may be different symptoms and consequences. Common problems with long-standing, pronounced symptoms are pressure ulcers (pressure sores), and contractures (painfully rigid joints) caused by spasticity (excessive muscle tension).

Whether or not life expectancy is impaired also depends heavily on the severity and, above all, on the location of the plegia. The life expectancy of paraplegics and quadriplegics is only slightly reduced (Niethard & Pfeil 2005). If several concomitant symptoms occur, e.g. if ventilation is necessary, the life expectancy may be more reduced.

Healing time/chances of recovery

The chances of recovery vary depending on the cause. If, for example, an incomplete paralysis is caused by a herniated disc, eliminating the cause (removing the intervertebral disc) may ease the pressure on the spinal cord and make the symptoms disappear. Residual symptoms may remain if the spinal cord has already been damaged by the pressure on the intervertebral disc.

If the cause cannot be eliminated, and the injury is thus permanent, there is currently no chance of a recovery. However, consistent rehabilitation assists in restoring functions, learning compensation strategies, and improving the patient’s quality of life.

Other complications or consequences

If the bladder function is impaired, especially if the bladder cannot be completely emptied, urinary tract infections are more likely. A catheter may be necessary if the patient is no longer able to independently empty his or her bladder.

Diagnosis: tetraplegia

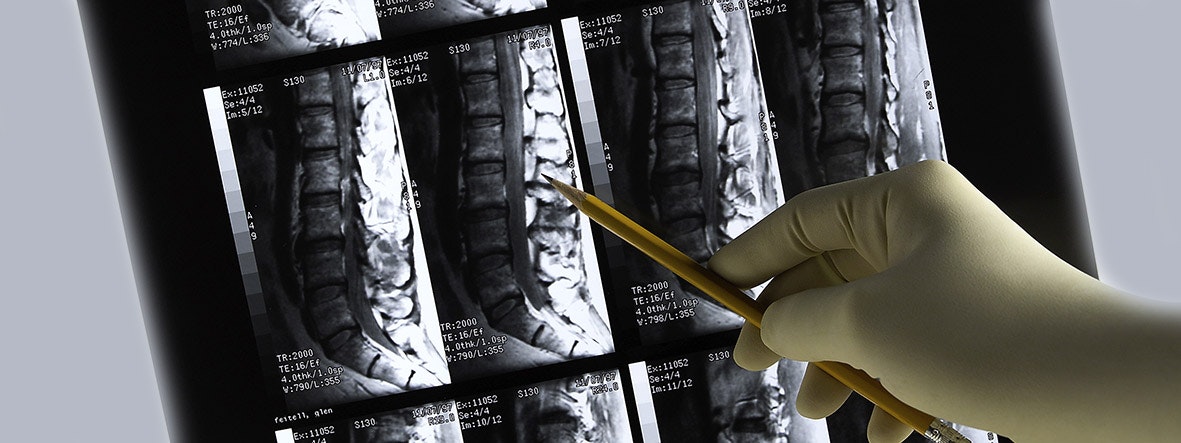

Imaging techniques such as CT, MRI, or X-ray are used to diagnose possible tetraplegia.

First and foremost, the diagnostic process must establish the cause of the tetraplegia. Initial hypotheses can be made based on the case history and a clinical neurological examination. Various examinations may be useful, depending on the suspected cause:

- X-ray, computed tomography (CT) to display the osseous structures, especially if an accident is suspected to be the cause

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for a more accurate assessment of the spinal cord

- Lumbar puncture to examine the cerebrospinal fluid

- Neurophysiological studies (evoked potentials - EVP) to assess nerve conductivity

- Examination of the blood supply and blood vessels, especially in traumatic injuries to the neck

- Blood tests

Treatment of tetraplegia

Acute tetraplegia, which is usually caused by an accident, must be treated immediately. Emergency services use an ambulance or a helicopter to transfer the patient to the trauma room in the nearest specialist hospital. The following occurs in the hospital:

- the diagnosis

- acute treatment of complications (intestinal obstruction, cardiovascular failure, etc.)

- surgery if necessary (in the case of bone fractures: immobilisation/plating)

- intensive care monitoring and follow-up

Surgery is also indicated if the tetraplegia is caused by a tumour or other mass (e.g. herniated disc). Routine treatment also includes special medication for inflammatory causes, tumours, coagulation disorders, or severe post-traumatic pain.

Symptomatic treatment of sexual, bladder, or sensory disorders (dysaesthesias) may be required at a later stage. Spasticity, which occurs at a later stage in the healing process, may also require treatment. This pathologically increased muscle tension can be treated pharmacologically (Botox, baclofen). The combination of pharmacological treatment and electrotherapy has proven to be beneficial (Cotoi et al. 2018). Early physiotherapy and occupational therapy are also particularly important for the treatment of symptoms.

Bladder and rectal disorders are alleviated to the greatest possible extent using compensatory techniques. The mostly spastic bladder can be controlled by an indwelling catheter, or by catheterisation several times daily using disposable catheters. Regular urological follow-up visits are particularly important in this case. The flaccid or spastic colon is compensated primarily by regulating the diet, and thus the stool consistency, and by digital stimulation.

Rehabilitation of tetraplegia

Physiotherapy, occupational therapy & further treatment

The therapy is already started as soon as possible during the inpatient hospitalisation. The goal of the therapy is to ensure the maximum independence of the affected person in their everyday life, as well as their social and professional reintegration.

Physiotherapy is mainly concerned with restoring functions, training specific activities, and restoring movement with or without aids. Depending on the severity of the damage, the focus may also be on independent use of a wheelchair or independent movement in bed. A balance between restorative and compensatory measures is the key to ensuring that the affected person can successfully master their daily routine.

Physiotherapy also serves to maintain and improve the pulmonary function. Since pneumonia is considered to be one of the more serious complications and represents a high risk, patients are treated in repeated rehabilitation phases. The consistent therapy

aims at improving or restoring functions, thereby minimising the risk of infection.

Physiotherapy and occupational therapy for (incomplete) tetraplegia

Occupational therapy focuses on independence, dressing and undressing, as well as household tasks. Especially in this setting, context factors (such as age, gender, fitness, home life, family environment, etc.) play an essential role

in the successful integration of what has been learnt into the daily routine. The provision of aids of any kind can also facilitate everyday life and increase the independence of the affected person.

Future leisure activities constitute another important aspect that is mostly covered by occupational therapy. The therapy sessions often aim to find new hobbies for those affected. Effective structuring of the newfound leisure time is essential, especially if the patient has lost the ability to work.

An interdisciplinary task is the prevention of secondary complications such as:

- pressure ulcers (bedsores) due to reduced mobility

- contractures (painfully rigid joints) due to excessive muscle tension (spasticity)

Whether in the therapy, at home, or in the nursing home, attention must be paid to warning signs. Timely intervention is essential, where required. Special mattresses and splints may be helpful in these cases.

Functional electrical stimulation for (incomplete) tetraplegia

Electrotherapy

The focus is on restoring functions for patients with incomplete tetraplegia The EMG-triggered functional electrical stimulation (EMG FES) enables the affected person to perform everyday exercises through multi-channel stimulation (Popovic et al. 2011).

Functional electrical stimulation is not only used to restore functions, but also to treat spasticity. The treatment is particularly advantageous in combination with Botox, as compared to Botox injections on their own (Cotoi et al. 2018).

Flaccid paralysis at the level of injury is usually the main concern for the affected person due to the strength deficit. The structure can be preserved and the muscle strength improved by stimulating with adapted currents (low frequency, long pulse duration) (Kern et al. 2010). Electrical stimulation may even be applied years after the spinal cord injury (Kern et al. 2002), and even in the case of complete denervation (Kern et al. 2017).

In this context, preventing pain in the subluxated shoulder is the main concern. Treatment with neuromuscular electrical stimulation may help stop the increasing muscle atrophy, which is caused by the (partial) denervation, and thus the subluxation (Koyuncu et al. 2010; Fil et al. 2011).

In the case of complete paralysis or severe damage, the focus is on supporting the upper limbs, which are sometimes still partially innervated. Stimulation should help to train the support function and a functional hand after tendon transplants (Bersch & Fridén 2016).

Functional electrical stimulation is also an important treatment method for patients with paraplegia (Th2-Th5) and quadriplegia (tetraplegia), since they can no longer voluntarily activate abdominal muscles. Stimulation can activate abdominal muscles, which are responsible for forced exhalation and coughing, thus making coughing possible (Gollee et al. 2008).

If you are interested in continuing education on functional electrical stimulation and wish for a STIWELL® training directly at your institute or online, please contact us

Find out how electrical stimulation with the STIWELL® can be used in the treatment of incomplete tetraplegia.

American Spinal Injury Association (1992). ASIA classification, Standards of neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. American Spinal Injury Association Chicago.

Bersch, I., & Fridén, J. (2016). Role of functional electrical stimulation in tetraplegia hand surgery. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation, 97(6), 154-159[CK1] .

Cotoi, A., Iliescu, A., Foley, N., Mirkowski, M., Harris, J., Dukelow, S., Knutson, J., Chae, J., Miller, T., Lee, A., Janssen, S. & Teasell, R. (2018). EBRSR Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation. Chapter 10. Upper Extremity Interventions, 91.

Fil, A., Armutlu, K., Atay, A. O., Kerimoglu, U., & Elibol, B. (2011). The effect of electrical stimulation in combination with Bobath techniques in the prevention of shoulder subluxation in acute stroke patients. Clinical rehabilitation, 25(1), 51-59.

Gollee, H., Hunt, K. J., Allan, D. B., Fraser, M. H., & McLean, A. N. (2008). Automatic electrical stimulation of abdominal wall muscles increases tidal volume and cough peak flow in tetraplegia. Technology and Health Care, 16(4), 273-281.

Kern, H., Carraro, U., Adami, N., Biral, D., Hofer, C., Forstner, C., ... & Paolini, C. (2010). Home-based functional electrical stimulation rescues permanently denervated muscles in paraplegic patients with complete lower motor neuron lesion. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 24(8), 709-721.

Kern, H., Hofer, C., Mödlin, M., Forstner, C., Raschka‐Högler, D., Mayr, W., & Stöhr, H. (2002). Denervated muscles in humans: limitations and problems of currently used functional electrical stimulation training protocols. Artificial organs, 26(3), 216-218.

Kern, H., Hofer, C., Loefler, S., Zampieri, S., Gargiulo, P., Baba, A., ... & Carraro, U. (2017). Atrophy, ultra-structural disorders, severe atrophy and degeneration of denervated human muscle in SCI and Aging. Implications for their recovery by Functional Electrical Stimulation, updated 2017. Neurological research, 39(7), 660-666.

Koyuncu, E., Nakipoğlu-Yüzer, G. F., Doğan, A., & Özgirgin, N. (2010). The effectiveness of functional electrical stimulation for the treatment of shoulder subluxation and shoulder pain in hemiplegic patients: A randomized controlled trial. Disability and rehabilitation, 32(7), 560-566.

Niethard, F. U., & Pfeil, J. (2005). Orthopädie. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme Verlag.

Popovic, M. R., Kapadia, N., Zivanovic, V., Furlan, J. C., Craven, B. C., & McGillivray, C. (2011). Functional electrical stimulation therapy of voluntary grasping versus only conventional rehabilitation for patients with subacute incomplete tetraplegia: a randomized clinical trial. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 25(5), 433-442.

Schweizer Paraplegiker Vereinigung (2012). Querschnittlähmung. Paradidact SPV Nottwil.