Multiple sclerosis (MS)

Multiple sclerosis, also known as encephalomyelitis disseminata (ED), is an autoimmune disease in which the body attacks its own nerve tissue in the brain and spinal cord. It creates inflammatory foci in the affected areas, which subsequently harden (sclerosis).

Learn more about multiple sclerosis in this article: What is multiple sclerosis (MS) and what are its symptoms? Definition, numbers, signs, diagnosis, progression & life expectancy, and treatment options at a glance. And much more...

What is multiple sclerosis?

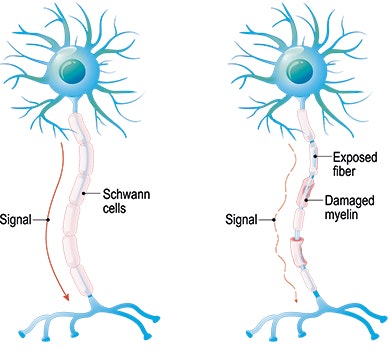

Multiple sclerosis (ICD-10 CODE: G35) is an autoimmune disease. This means that the body attacks its own tissue, in this case, the myelin sheath (electrically insulating outermost layer of nerve fibres). This causes inflammation and hardening (sclerosing) of the affected myelin sheath and slows signal transmission as a result. This damage may occur in various places in the brain (typically in the area around the cerebrospinal fluid spaces), and/or in the spinal cord. Due to these distributed (disseminated) inflammations in the central nervous system (encephalomyelitis), the disease is occasionally called encephalomyelitis disseminata (ED).

MS is the most common inflammatory disease affecting the central nervous system. It is usually diagnosed when people are in their 20s-40s, and it is nearly three times more common in women than in men. There are approx. 2 million patients worldwide (WHO 2008), and approx. 200,000 of these patients live in Germany (Petersen et al. 2014).

Symptoms of multiple sclerosis

The insulating layer of nerve fibres (myelin sheath) is attacked by the immune system (white blood cells, T cells) and is destroyed as a result (through demyelination of axons). This leads to a misguided immune reaction which causes inflammation (mainly in the white matter). As a result, the nerve conduction, i.e. the transmission of information to and from the brain, is slowed down.

This process causes different clinical symptoms depending on the location of damage:

- Cerebrum: Muscle weakness (pareses), disturbed sensation of touch or depth (sensory disorders), pathologically increased muscle tone (spasticity), cognitive disorders, depression, fatigue

- Cerebellum: Speech disorders, balance disorders, coordination disorders, tremor (rhythmic trembling of muscles), dizziness

- Brain stem: Temperature sensation disorders, paralysis, double vision

- Spinal cord: Major sensory disorder, muscle spasms, muscle weakness (paresis), tetraplegia, bladder and rectal disorders, sexual disorders (impotence, decreased libido, decreased sensitivity)

Other clinical symptoms of multiple sclerosis:

- Optic nerve inflammation (optic neuritis)

- Sudden (paroxysmal) phenomena and involuntary movements:

- Motor: Increased muscle tone (spasms/dystonia), speech disorders (dysarthria), coordination disorders (ataxia), myokymia (short tetanic contraction in skeletal muscles), myoclonus (segmental, rapid, involuntary muscle twitching)

- Sensory: Nerve pain (neuralgia), sensory disorder (paraesthesia) such as the Lhermitte's sign (paraesthesia in the neck during passive bending of the head), itching (pruritus)

- Various: epileptic seizures, pathological laughter and crying, urge to urinate

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Fatigue (state of fatigue/exhaustion that is not related to the previous activity)

- Eye movement disorder (effects: double vision, nystagmus)

- Uhthoff's phenomenon: a short-term worsening of nerve conduction with increased body temperature or outside temperature, which causes, for example, an increase in visual impairment (as described by Uhthoff), paralysis, or a sensory disorder.

MS may cause different symptoms depending on the location and extent of the damage. Frequent symptoms are muscle weakness (paresis), increased muscle tone (spasticity), sensory disorders, coordination and balance disorders. Typical for MS are fatigue (persistent exhaustion) and a worsening of symptoms when the body temperature or outdoor temperature rises (Uhthoff's phenomenon).

First signs of multiple sclerosis

An inflammation of optic nerves (optic neuritis) is often the first symptom of multiple sclerosis. Once the symptoms of this inflammation have subsided on their own, usually after one to two weeks, most affected persons do not seek medical attention.

Thus optic neuritis is often overlooked, mainly because of its short duration.

Symptoms of optic nerve inflammation:

- Usually unilateral visual impairment, ‘as if seeing through fog or frosted glass’

- Pain (on movement) in or behind the eye

- Impaired colour perception (especially red) and contrast sensitivity

- Impaired pupillary response

- increasing within hours to days

Initial remedy upon appearance of symptoms

If you suddenly experience a visual impairment (first signs) or other symptoms (muscle weakness, etc.), see a physician immediately. It may not necessarily be multiple sclerosis, but the sudden onset of neurological symptoms must always be considered an emergency, which makes it essential to see a physician.

If you experience symptoms during a relapse (with diagnosed MS), inform the neurologist who is treating you. It is most likely that relapse therapy (pharmacological therapy/treatment) will be necessary. If you lose your ability to walk or drive because of the relapse, notify your relatives or the emergency services to bring you to a neurologist or a hospital. Do not try to get there on your own.

If symptoms worsen (for patient with diagnosed MS) due to excessive heat or exercise (Uhthoff's phenomenon), it helps to cool the body by applying ice or cool packs. This should make the symptoms disappear in a few minutes or hours.

Diagnosis: multiple sclerosis

Since the symptoms of multiple sclerosis can be very varied and the diagnosis is very complex, an experienced neurologist and some examinations are needed in order to make a reliable diagnosis. The following examinations are usually part of the diagnostic process:

- detailed medical history (case history)

- clinical neurological examination

- magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- examination of the cerebrospinal fluid by means of lumbar puncture

- evoked potentials (measurement of nerve conductivity)

A differential diagnosis (distinguishing it from other diseases) is important for MS. If other diseases can be ruled out as the cause of the symptoms, specific criteria (McDonald criteria) can help to ensure the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Once

the diagnosis has been made, the EDSS (Expanded Disability Status Scale) serves as the clinical scale for assessing the severity of MS.

The MRI scan shows small point-shaped lesions. However, the MRI scan alone is insufficient for a reliable diagnosis.

McDonald criteria

These criteria help physicians to diagnose MS earlier and more reliably. They consider spatial and temporal distribution (dissemination) of relapses and lesions, along with additional examinations. The advancement of expertise and the ever-improving imaging

techniques (MRI) enabled the new, improved revision of the McDonald criteria in 2017 (Thompson et al. 2018).

EDSS (Expanded Disability Status Scale)

EDSS is used as a clinical scale for assessing the severity of MS. The scale ranges from 0 to 10 in 0.5 increments. 0 represents a normal neurological examination. An increasing score correlates with increasing physical impairment (Marks 2008).

Some excerpts from the ESDSS (Marks 2008):

- 0 Normal neurological examination in all functional systems

- 5.0 Ambulant without aid for about 200 metres, disability severe enough to affect daily activity; full ability to work no longer possible

- 7.0 Unable to walk more than 5 metres even with aid, essentially restricted to wheelchair

- 8.5 Essentially bedridden for most of the day

The diagnostic process for MS is complex and often protracted, since other diseases must first be ruled out as the cause of symptoms. Once this has been done, special criteria (McDonald criteria) support a reliable diagnosis. Once the diagnosis has been confirmed, the EDSS (Expanded Disability Status Scale) is used to assess the severity of the disease.

Causes of multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease where the body attacks the central nervous system (upper motor neuron = spinal cord and brain), causing inflammation and plaques (patchy changes) in the affected areas. However, the exact cause (aetiology) of

this process is still unclear.

However, there are several factors that play an important role in the genesis (pathogenesis) of the disease (multifactorial genesis).

Since MS is an autoimmune disease, which means that the body attacks itself, the immune system is probably of central importance. More specifically, MS causes T cells to attack and destroy the myelin sheath of nerve fibres (demyelination of axons), provoking a misguided immune response. This causes inflammatory reactions, and slows down the flow of information to and from the brain.

This can be demonstrated by various examinations (diagnostics), and results in different symptoms, depending on the location and extent of damage.

Due to the genesis (pathogenesis) of MS, various hypotheses about its cause (aetiology) focus on the immune system. However, it is necessary to research and examine these hypotheses in more detail. Current considerations focus on infection, hygiene, or intestinal bacteria as possible causes.

Although MS is not a classical hereditary disease, there is a certain genetic and local predisposition (depending on the latitude - risk factors). This suggests that vitamin D metabolism may play a role. However, further research is needed to establish whether there is a causal relationship.

Risk factors for multiple sclerosis

Factors that play a central role in the genesis of multiple sclerosis may be considered risk factors (causes of MS) in the broadest sense. However, since the cause of MS has not yet been established, it is not possible to provide information on specific risk factors.

Observations and current statistics show a correlation between an increasing risk of MS and increasing latitude. People living further away from the equator have a higher risk of developing MS than those who live near the equator. The Inuit are an exception. This may be due to their diet, which is rich in vitamin D. In the case of migrants, the time of their migration plays an essential role. If they migrate before they are 15 years of age, they face the same risk as the inhabitants of the host country. If they migrate later in life, then the risk is the same as in their country of origin.

Progression/progressive forms of multiple sclerosis

The progression of multiple sclerosis differs for each affected person. However, there are several essential progressive forms:

- Clinically isolated syndrome (CIS): This is the first occurrence of neurological symptoms due to demyelination in the brain or spinal cord. This may lead to MS, but this does not have to be the case. A diagnosis of MS is considered confirmed if neurological symptoms appear for the first time and tests discover older lesions in other locations, or other active inflammatory foci.

- Relapsing-Remitting MS (RRMS): Relapses occur in irregular and unpredictable intervals. In the beginning, there is usually complete remission of neurological symptoms, while there is often only partial remission at a later stage.

- Primary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis (PPMS): PPMS is characterised by a progression of the disease without relapses. The disability progresses steadily and gradually.

- Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis (SPMS): This form also has a relapsing progression; however, relapses occur during a constant increase in disability. In some cases, relapsing-remitting progressive forms (RR) change into a

secondary progressive form (SP) after a few years.

A relapseis a set of neurological symptoms that

... develop within hours or days

... last for longer than 24 hours

... occur after at least 30 days from the last relapse

... are not accompanied by fever or infections

How long does the treatment take?

The therapy consists of pharmacological treatment and rehabilitation. The duration of therapy depends very much on the form of MS and on the level of physical impairment.

For example, an acute attack may be treated for only 3-5 days, while the disease-modifying therapy (medication, injections, etc.) is continuous and lifelong. The above also applies to rehabilitation. Rehabilitation (inpatient, for several weeks) may be

useful following a relapse. The chronic progressive form of MS often requires outpatient therapy. It can be performed in parallel to the affected person’s daily routine.

Long-term damage & life expectancy

In principle, one can fully recover even after the onset of symptoms. The recovery depends on the degree of inflammation or the severity of symptoms, the timeliness and extent of the subsequent treatment, and the speed with which the disease progresses.

The affected person may be able to regain mobility with the help of a walking stick, a rollator, or a wheelchair. Whatever the individual progression of MS, the affected person’s life expectancy will probably not be affected. The life expectancy of people with MS is only slightly lower than that of the general population.

Normally, multiple sclerosis is different in every affected person. It may progress gradually and/or worsen during relapses. Consistent therapy aims at maintaining independence with only slightly decreased life expectancy.

Pharmacological therapy/treatment of multiple sclerosis

The pharmacological therapy for MS has two mainstays: the disease-modifying therapy and the relapse therapy. In the event of an acute relapse, the patient receives cortisone (glucocorticoids, such as methylprednisolone) intravenously

for three to seven days. In the case of severe relapses, the patient may require an oral tapering phase over two weeks. If treatment with glucocorticoids fails, plasma separation (plasmapheresis) may be performed as an alternative.

Disease-modifying, immunomodulatory treatment with interferon beta preparations and glatiramer acetate is performed for the clinically isolated syndrome and moderate relapsing-remitting MS. These preparations are injected subcutaneously. For some years, however, oral disease-modifying medication has also been used in relapsing-remitting MS (dimethyl fumarate and teriflunomide). All of these medications have an anti-inflammatory effect on the immune system, and may thus delay the progression of the disease.

Patients who are not adequately protected against deterioration by long-term medication as well as patients with highly active relapsing-remitting progression are given fingolimod (pill) or natalizumab (infusion). The medications serve to keep inflammatory cells in the lymph nodes, or away from the brain and spinal cord. Alemtuzumab (infusion), which is used to treat T-cell lymphomas, was approved as an alternative treatment several years ago. It acts directly on the surface antigen of immunocompetent cells (including T cells).

Non-selective immunosuppressants, such as mitoxantrone (infusion), may be used as second-line therapy for highly active relapsing-remitting MS or secondary progressive MS. Interferon beta may be used for secondary progressive MS with superimposed relapses.

The goals of pharmacological treatment and also of rehabilitative therapy are as follows:

- treating active MS lesions

- delaying the progression of the disease

- inhibiting inflammation & oxidative stress

- supporting neuronal growth

Learn more about rehabilitation for patients with multiple sclerosis in the next section.

Rehabilitation of patients with multiple sclerosis

Physiotherapy - occupational therapy - speech therapy

In addition to pharmacological treatment, rehabilitation is the second mainstay for correcting functional deficits caused by multiple sclerosis. Rehabilitative measures are designed to improve patients’ functional abilities, support their independence, and maintain their usual participation in social life.

All measures should be adapted to the situation of the affected person (occupation, partnership, domestic life, etc.), while taking the chronic disease into consideration. The recent paradigm shift in the therapy recommends starting at an early stage (if desired by the patient), since early treatment can significantly improve the patient’s quality of life.

The following recommendations can be made for the therapies (physiotherapy/occupational therapy/speech therapy):

- Training intensity

- Low intensity & longer duration 3-4 times per week, 20-30 min.

- New approaches: first studies on high-intensity training demonstrate an improvement in performance (Campbell et al. 2018)

- Endurance training to improve aerobic capacity

- Resistance training to improve muscle strength

- Supporting independent training from the outset

- Correct choice between a restorative and a compensatory approach

- Psychological aspects should not be ignored

- Bladder/rectum and sexual disorders should not be taboo topics, but should be considered in the therapy.

- Set joint (interdisciplinary) goals related to activities of daily living (ADL)

- Therapy goals: repeated planning process through target evaluation (assessments) and, if necessary, reformulation

- The therapist should be familiar with current treatment methods and the current state of research. This is particularly important in the case of multiple sclerosis.

Different therapies may be indicated, depending on the symptoms caused by MS. Physiotherapy is mainly concerned with the re-learning of functions and activities. Occupational therapy focuses on the daily application of these activities. Speech therapy deals with speech and swallowing disorders. However, several of these treatment options are often prescribed at the same time to address all needs of the patient.

Rehabilitation is essential to restore functions. Physiotherapy, occupational therapy, or speech therapy can be useful, depending on the area of life which causes the greatest problems (mobility, everyday life, speech, etc.)

Electrotherapy

Various therapies involving electrotherapy can be used in the rehabilitation process for the treatment of a wide variety of MS symptoms. Some electrotherapy devices can also be rented for home therapy (such as the STIWELL®, see home-based therapy), so

that the patient can continue treatment, after training, even without the therapist.

STIWELL® therapy | grasp and release (FES)

STIWELL® therapy | stand up (FES)

Most limitations experienced by patients with MS result from the disrupted signal transmission from the brain via the neural pathways to the muscles. Functional electrical stimulation may help enhance signal transmission and thus treat symptoms such as

muscle weakness (pareses). EMG-triggered multi-channel electrical stimulation makes it even possible to re-learn entire motion sequences, such as grasping or walking.

Biofeedback training may help improve coordination of patients with MS. The visual feedback supports re-learning in the event of sensory disorders. Biofeedback can also be used for pelvic floor training for patients with bladder/rectal disorders.

However, electrotherapy is not only useful in the early phase. It can also be used in a later rehabilitation phase, when spasticity is in the foreground, to influence the increased muscle tension. Frequent repetition in a functional context facilitates

therapeutic success according to the principles of motor learning.

If you are interested in continuing education on functional electrical stimulation and wish for a STIWELL® training directly at your institute or online, please contact us

Find out how electrical stimulation with the STIWELL® can be used in the treatment of multiple sclerosis.

Campbell, E., Coulter, E. H., & Paul, L. (2018). High intensity interval training for people with Multiple Sclerosis: a systematic review. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 24, 55-63.

Marks, D. (2008). Multiple Sklerose Schweregrad bestimmen. physiopraxis, 6(09), 38-39.

Petersen, G., Wittmann, R., Arndt, V., & Göpffarth, D. (2014). Epidemiologie der Multiplen Sklerose in Deutschland. Der Nervenarzt, 85(8), 990-998.

Thompson, A. J., Banwell, B. L., Barkhof, F., Carroll, W. M., Coetzee, T., Comi, G., ... & Fujihara, K. (2018). Diagnosis of multiple sclerosis: 2017 revisions of the McDonald criteria. The Lancet Neurology. 17(2), 162-173.

World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Multiple Sclerosis International Federation (MSIF). Atlas: Multiple Sclerosis Resources in the World 2008.