Cruciate ligament rupture

A cruciate ligament rupture means a rupture of one of the two cruciate ligaments in the knee joint. It causes instability in the knee joint as well as swelling and pain, which appear especially when the knee is subjected to stress. Cruciate ligament ruptures can be treated surgically or conservatively (physiotherapy/electrotherapy). Consistent rehabilitation is necessary in each case.

What is a cruciate ligament rupture? What treatment or therapy methods are available and what are the long-term chances of recovery? Definition, numbers, causes, and diagnosis at a glance ...

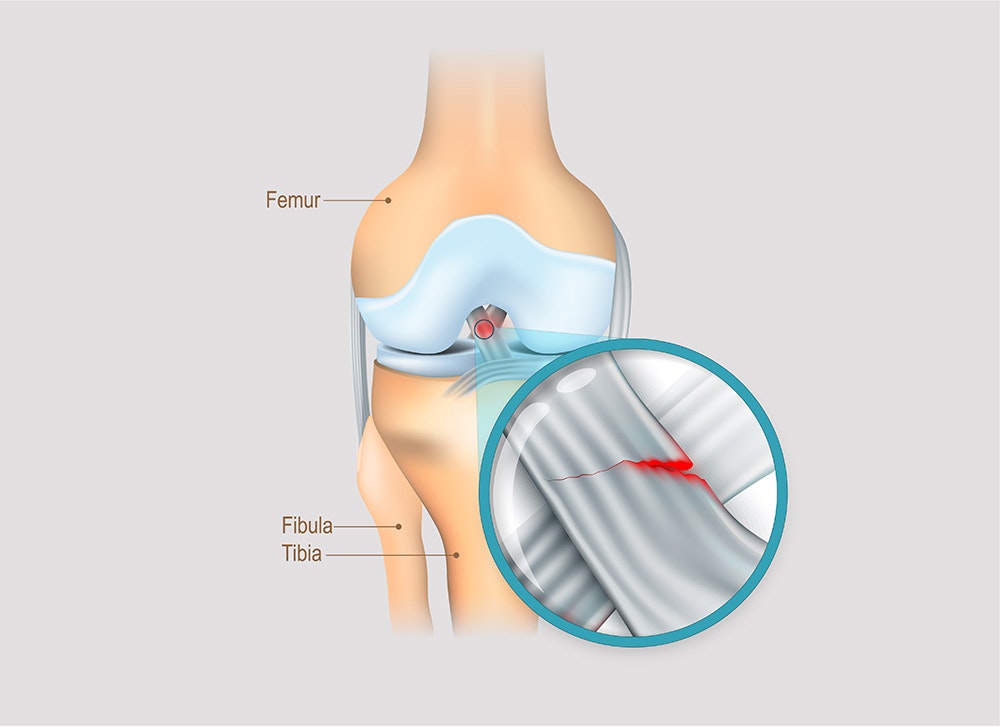

What is a cruciate ligament rupture?

A cruciate ligament rupture is a partial or complete rupture of one of the two cruciate ligaments.

There are two cruciate ligaments in the knee joint. They consist of an anterior and a posterior cruciate ligament. They run obliquely and cross each other. Hence the term cruciate ligament.

If the anterior cruciate ligament is affected, the injury is called an ACL injury. Analogously, when the posterior cruciate ligament is affected, it is called a PCL injury.

Symptoms of a cruciate ligament rupture

Due to the stabilising function of the cruciate ligament, the knee joint becomes unstable when the ligament is torn. As with any injury, there is also swelling (joint effusion), pain, and redness or a burning sensation. The swelling and instability in the knee subsequently lead to restricted movement in the joint, and thus to functional impairments with resulting difficulties in everyday life.

The symptoms worsen under stress and improve with immobilisation. Those affected describe the feeling of insecurity when moving, especially when walking, as the most uncomfortable aspect of the injury. This is known in technical terms as ‘giving way’.

Whether surgery is necessary or conservative rehabilitation is sufficient must be decided on a case-by-case basis. Usually, however, the larger or more complex the injury (isolated partial tear up

to unhappy triad), the sooner surgery must be performed.

First aid for cruciate ligament rupture

In many cases, a loud snap can be heard when a tear occurs. This is associated with severe pain. It is important to keep calm and not to move the knee. If necessary, the knee can be splinted and cooled.

The affected person should be taken to hospital as soon as possible, preferably in a lying position, for example, by the emergency services, since the knee would often have to be bent sharply if transported in a car. Not only would this be painful, it could also make the injury worse.

First aid for a cruciate ligament rupture: Keep calm - do not move the affected knee - cool the knee and contact the emergency services.

Diagnosis: cruciate ligament rupture

The initial diagnosis is made based on a clinical examination. The clinical examination includes a detailed palpation of the effusion, the joint space, and the collateral ligaments, as well as a mobility test of the knee joint and, if necessary, an analysis of the gait pattern. Joint stabilisation tests (meniscus, collateral ligament, and capsule tests) are also carried out.

The stability is then checked by comparing the two sides. Various tests can help assess the strength of the cruciate ligaments (Hepp & Locher 2014):

- Drawer test

The knee is flexed by 90°. The physician then moves the lower leg forwards in parallel (anterior tibial translation). If the play is larger than in the unaffected side, i.e. there is a front drawer sign, this indicates a tear in the anterior cruciate ligament. If the lower leg can be pushed backwards excessively, the posterior cruciate ligament is likely to be torn.

- Lachman test

The Lachmann test is similar to the drawer test in terms of execution and assessment. In the Lachmann test, however, the flexion position is 20-30°, and the degree of displacement is assessed in 3 grades with documentation of the stop (fixed stop - soft stop - no stop).

- Pivot-shift test (subluxation test)

When the extended knee is rotated internally during this test, the pivot point, i.e. the lower leg, shifts forward. If the hip is then flexed, the tibia is suddenly shifted due to the muscle tension. There are 3 grades here as well.

If the clinical test shows any abnormal findings, an imaging technique is carried out for further clarification. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is usually performed in this case to rule out any concomitant injuries (meniscus/collateral

ligament). An X-ray is taken if an avulsion fracture is suspected (Herbort & Lobenhoffer 2018).

Causes of a cruciate ligament rupture

Cruciate ligament injuries occur between the ages of 15 and 25 with a frequency of 1 per 1000 inhabitants (Mehl et al. 2018), with men more likely to be affected. Most of the injuries occur during sports, especially ‘stop-and-go’ sports, or sports that are performed at high speed, such as:

- football

- handball

- basketball

- skiing

- martial arts

- kitesurfing, etc.

They are often ‘non-contact’ injuries, i.e. injuries that are not caused by impact with another person. The underlying injury mechanism is mostly a combination of maximum stress in:

- Hyperextension or tibial translation (displacement of the lower leg)

- Rotation movement: internal/external rotation (twisting of the knee joint)

- Valgus deformity (knock knees)

- Deceleration (sudden stop)

In rare cases, injuries may also occur with the knee bent. Depending on the force acting on the knee joint, the severity of the injury can be classified in ascending order, from an isolated cruciate ligament tear to complex injuries of the capsule-ligament apparatus (meniscus, collateral ligament, etc.)

The therapy for a cruciate ligament rupture depends on various factors. Both conservative and surgical treatment may be considered.

Therapy for a cruciate ligament rupture

Generally, a distinction is made between a conservative and a surgical approach. Conservative treatment means that an invasive procedure (e.g. surgery) is not used. However, all other rehabilitative measures and pharmacological treatment are used. Whether surgery is necessary depends on various factors:

- age

- presence of other injuries

- physical activity in everyday life (sedentary activities vs. sports)

- instability of knee joint

Surgery should also be considered in the case of sustained instability, or when conservative therapy fails. Various surgical options are available (Herbort & Lobenhoffer 2018):

- reconstruction with a ligament graft (using patient's own tissue)

- fixation (fixation of the torn cruciate ligament using sutures and screws)

- allograft (tendons from deceased donors)

The treating physician decides which surgical method to choose for each patient. In many cases, however, reconstruction with a ligament graft is used. It involves removing part of a tendon to use it as a ‘substitute’ cruciate ligament. Grafts can be taken from the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons (STG), patella tendon (BTB), or the quadriceps tendon. The tendon is secured with drill tunnels and bolts, and is thus very stable.

Healing time & process for a cruciate ligament rupture

The healing time is individual and varies from patient to patient. Generally, the more complex an injury is (e.g. unhappy triad, avulsion, etc.), the longer the healing time.

After the acute injury, the stress on the knee must often be relieved (with and without surgery) for about two weeks with the help of crutches and a splint (or a limited range of motion). Usually, the affected person is able to play sports again after a short time. If the rehabilitation is good, the patient can start relaxed running training after 6 weeks, and can resume full training after 3 months. However, ‘stop-and-go’ sports should be avoided for at least six months.

The right choice between conservative and surgical treatment as well as thorough rehabilitation (physiotherapy/electrotherapy) are key to a positive and rapid healing process.

How long will I have to stay in hospital after surgery?

Usually, one has to stay 1-3 days in hospital. These times vary depending on the severity of the pain, whether there are complications, and how far the mobilisation has progressed (climbing stairs should now be possible).

Functional electrical stimulation helps rebuild muscles and restore coordination after a cruciate ligament rupture.

Treatment of a cruciate ligament rupture

Rehabilitation therapy (physiotherapy, electrotherapy) can be carried out after surgery or as standalone treatment. Purely conservative treatment (without surgery) is generally only possible in the case of isolated cruciate ligament ruptures if various factors apply (Fink et al. 2001):

- minor instability (e.g. in the Lachman test)

- no feeling of instability

- low load requirements or low activity level

Non-surgical therapy is also preferred for older patients with good treatment results when there is low activity level and low instability. However, there is no age limit for a surgical reconstruction. In the case of conservative treatment, close monitoring is recommended so that surgery can be performed promptly if the conservative treatment fails (preventing long-term damage).

Conservative treatment corresponds to post-operative treatment. The focus is on active rehabilitation with adjuvant therapeutic measures:

- physiotherapy

- electrotherapy

- knee orthosis (splint to limit movement)

- walking aids to reduce stress (if necessary)

- pain management (if necessary)

Physiotherapy

Intensive physiotherapy is particularly important for the healing process. The therapy should start as early as possible during the hospital stay. This is where an early functional therapy starts, where the patient learns to walk using crutches and climb the stairs. Strengthening exercises must also be started immediately because if the thigh is not activated, it quickly loses mass and thus strength.

Strength training runs through the entire rehabilitation phase, and is subsequently accompanied by intensive coordination and balance training. A gradual build-up of load is important. It may vary depending on other injuries. The constant expansion of movement range through active and passive movement training (mobilisation of the knee) is a key aspect of the therapy. In the initial phase, especially if the knee is still very swollen, lymphatic drainage can be useful.

If those affected participate in competitive sports, the ‘back-to-sports’ or ‘back-to-competition tests’ are recommended (cf. Herbst et al. 2015; Hildebrandt et al. 2015). They serve to check if the function and resilience of the affected leg is adequate for the respective sport. These tests are also carried out by physiotherapists.

Electrotherapy

Functional electrical stimulation can help restore strength and coordination more quickly after a cruciate ligament rupture. Special programmes are used for muscle strengthening and are particularly important in the initial phase. The EMG-triggered electrical stimulation can be subsequently used to support the muscles in a functional context, i.e. in movement exercises.

Some electrical stimulation devices also enable coordination training. This is supported by biofeedback, i.e. feedback on the muscle tension, which helps to improve body awareness. The feedback can be given in a fun context (such as car racing), which also increases motivation, especially during a longer rehabilitation.

If you are interested in continuing education on functional electrical stimulation and wish for a STIWELL® training directly at your institute or online, please contact us

Find out how functional electrical stimulation with the STIWELL® can be used to treat a cruciate ligament rupture.

Fink, C., Hoser, C., Hackl, W., Navarro, R. A., & Benedetto, K. P. (2001). Long-term outcome of operative or nonoperative treatment of anterior cruciate ligament rupture-Is sports activity a determining variable?. International journal of sports medicine, 22(04), 304-309.

Hepp, W. R., & Locher, H. A. (2014). Orthopädisches Diagnostikum. Georg Thieme Verlag.

Herbort, M., & Lobenhoffer P. (2018). Vordere Kreuzbandruptur. S1-Leitlinie der deutschen Gesellschaft für Unfallchirurgie.

Herbst, E., Hoser, C., Hildebrandt, C., Raschner, C., Hepperger, C., Pointner, H., & Fink, C. (2015). Functional assessments for decision-making regarding return to sports following ACL reconstruction. Part II: clinical application of a new test battery. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy, 23(5), 1283-1291.

Hildebrandt, C., Müller, L., Zisch, B., Huber, R., Fink, C., & Raschner, C. (2015). Functional assessments for decision-making regarding return to sports following ACL reconstruction. Part I: development of a new test battery. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy, 23(5), 1273-1281.

Mehl, J., Diermeier, T., Herbst, E., Imhoff, A. B., Stoffels, T., Zantop, T., ... & Achtnich, A. (2018). Evidence-based concepts for prevention of knee and ACL injuries. 2017 guidelines of the ligament committee of the German Knee Society (DKG). Archives

of orthopaedic and trauma surgery, 138(1), 51-61.