Pareses

A paresis is an incomplete paralysis of a muscle, i.e. the muscle is weakened. If the muscle can no longer be moved at all, it is called a complete paralysis or plegia. Both forms are caused by damage to the afferent nerve.

What are the forms of paresis and what treatment or therapy methods are available? Definition, diagnosis, and progression at a glance ...

What is a paresis?

A paresis refers to the incomplete paralysis of a skeletal muscle, as opposed to a plegia, which means complete paralysis. It is caused by damage to the afferent motor nerve. The neurological disorder manifests itself as decreased muscle strength.

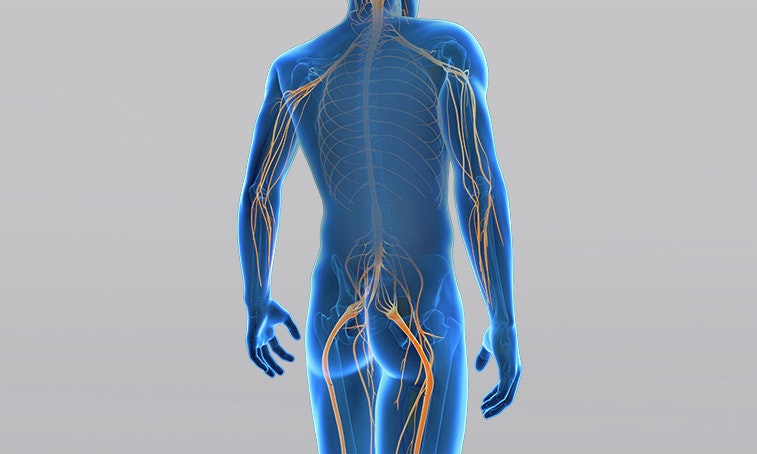

Pareses can be classified and described in different ways. On the one hand, they can be classified according to the number of damaged nerves or affected limbs and, on the other hand, according to the location of nerve damage in the body.

The location of the damage determines which of two forms exists:

- Central paresis

Damage to the nerve between the brain and the anterior horn cell of the spinal cord (upper motor neuron).

- Peripheral paresis

Damage to the nerve between the anterior horn cell of the spinal cord and the neuromuscular junction of the muscle (lower motor neuron).

Peripheral pareses can affect one or more nerves. Examples of isolated pareses are pareses of the radial, peroneus, or facial nerve. Damage to several nerves in the area of a nerve plexus is called plexus paresis. A distinction is made between a brachial plexus palsy (brachial plexus) and a lumbar plexus palsy (lumbar plexus).

Central pareses are classified according to the affected limb:

- Monoparesis

The incomplete paralysis affects only one limb, e.g. one arm.

- Paraparesis

Both legs are paralysed; arms are not affected.

- Hemiparesis

The arm and leg of one side of the body are partially paralysed.

- Tetraparesis

It involves partial paralysis of all four limbs (arms and legs) as well as impaired control over the torso and head.

In the case of central pareses, paralysed muscles are always on the side opposite to the brain damage. This means that damage to the left brain hemisphere paralyses the right side of the body and vice versa.

In the case of peripheral paralyses,

the paresis is always on the same side as the injury.

Causes of a paresis

The paresis is caused by damage to the motor nerve which initiates muscle movement. The nerve can be damaged by pressure, accidents, infarctions or haemorrhages in the brain, or along its peripheral course. Pressure damage is often caused by tumours or herniated discs, which inhibit signal transmission via the spinal canal (vertebral canal).

Pareses usually occur with the following conditions:

- Tetraplegia

- Multiple sclerosis

- Infantile cerebral palsy (early childhood brain damage)

- Stroke

- Traumatic brain injury

- Herniated disc

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Tumours

Central causes often cause a combination of incomplete paralyses (pareses) and complete paralyses (plegias) of individual muscles. For example, in the case of an incomplete tetraplegia caused by a spinal cord injury at chest level, torso muscles may only

be slightly affected, whereas the legs may be paralysed.

Diagnosis & degrees of paresis

Paresis is diagnosed on the basis of a clinical examination, imaging technique, and specific additional tests which are optional.

Paralyses are characterised by reduced muscle strength. For this reason, various scales are used to evaluate muscle strength in order to assess the degree of paralysis. The most common assessment is the scale of the Medical Research Council (MRC). It awards points from 0 to 5 per muscle or per movement. 0 points stand for a complete paralysis (plegia); 5 points mean that the muscle contracts normally against full resistance.

Electromyography (EMG) and electroneurography (ENG/NLG) are used to examine nerve conduction velocity and muscles in more detail. They may play an important role when it comes to determining the cause. If central damage is suspected, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can provide more information.

Progression of a paresis

If the cause of the nerve damage cannot be corrected, the continuous paralysis usually causes a loss of muscle mass (atrophy). It may also cause abnormalities of the connective tissue (fibrosis) in muscle fibres and increased fat deposits. The extent of atrophy and fibrosis is linked to the severity of the paralysis. Thus there is a relatively rapid loss of muscle mass in the case of severe paralysis.

Depending on the extent of the paresis, spasticity (increased muscle tension) is seen in the case of central damage because the brain cannot adequately control the spinal cord. This is why multiple sclerosis or a stroke often causes spastic paresis. The stronger the paresis, the stronger the spasticity. The combination of diminished muscle strength and increased muscle tension usually causes limited joint mobility, which may result in joint stiffness (contractures) over time.

Therapy of a paresis

Functional electrical stimulation can be perfectly combined with activities of daily living.

In the case of central pareses, such as those caused by a stroke or a traumatic brain injury, the rehabilitation is adapted to the patient's goals according to the principles of motor learning. Frequent repetition trains practical activities such as grasping or walking, which are limited due to paresis (Hauptmann & Müller 2011). In this case, the EMG-triggered electrical stimulation may help reinforce the movement.

With the help of functional electrical stimulation, training at home is possible after a briefing by the patient’s therapist. This helps to achieve the recommended therapy frequency of 5 exercise sessions of 30-45 minutes per week (Platz 2011).

If the peripheral nerve is damaged, which means that the muscle is partially denervated, a combination of active exercises and electrical stimulation is useful. Special current forms (low frequency, long pulse duration) can stimulate the muscle directly.

This can prevent atrophy/degradation of muscle sections that are no longer supplied by the nerve (Kern et al. 2010), and support nerve regeneration (Gordon et al. 2016).

If you are interested in continuing education on functional electrical stimulation and wish for a STIWELL® training directly at your institute or online, please contact us

Find out how functional electrical stimulation with the STIWELL® can be used in the treatment of pareses.

Gordon, T., & English, A. W. (2016). Strategies to promote peripheral nerve regeneration: electrical stimulation and/or exercise. European Journal of Neuroscience, 43(3), 336-350.

Hauptmann, B. & Müller, C. (2011). Motorisches Lernen und repetitives Training. In: Nowak, D. (Hrsg.) Handfunktionsstörungen in der Neurologie. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Verlag, 214-223.

Kern, H., Carraro, U., Adami, N., Biral, D., Hofer, C., Forstner, C., ... & Paolini, C. (2010). Home-based functional electrical stimulation rescues permanently denervated muscles in paraplegic patients with complete lower motor neuron lesion. Neurorehabilitation and neural repair, 24(8), 709-721.

Platz, T. (2011). Rehabilitative Therapie bei Armlähmungen nach einem Schlaganfall. Patientenversion der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Neurorehabilitation. Bad Honnef: Hippocampus Verlag.